Digitalization, done right, can equip governments to improve revenue collection and spending efficiency.

Digitalization is a transformative force as powerful as the advent of the printing press in the 15th century or electricity in the 19th. Yet some governments have been slow to harness the potential of digital technology to improve delivery of public services and strengthen public finance.

A two-pronged policy approach is required—connecting unconnected households to the internet and accelerating and strengthening the adoption of digital solutions in the public sector. We outline strategies for pursuing these policies in a new staff discussion note on government technology, or govtech.

Encouraging digital adoption

Emerging and developing countries have the most potential to leapfrog their development trajectory by adopting digital technologies. These countries lag considerably behind in internet connectivity, a key enabler for adopting and using digital technologies. Globally, about 2.7 billion people still need to be connected. Within countries, a digital divide persists across age and gender. Bridging this divide and benefiting from digitalization takes adequate digital infrastructure.

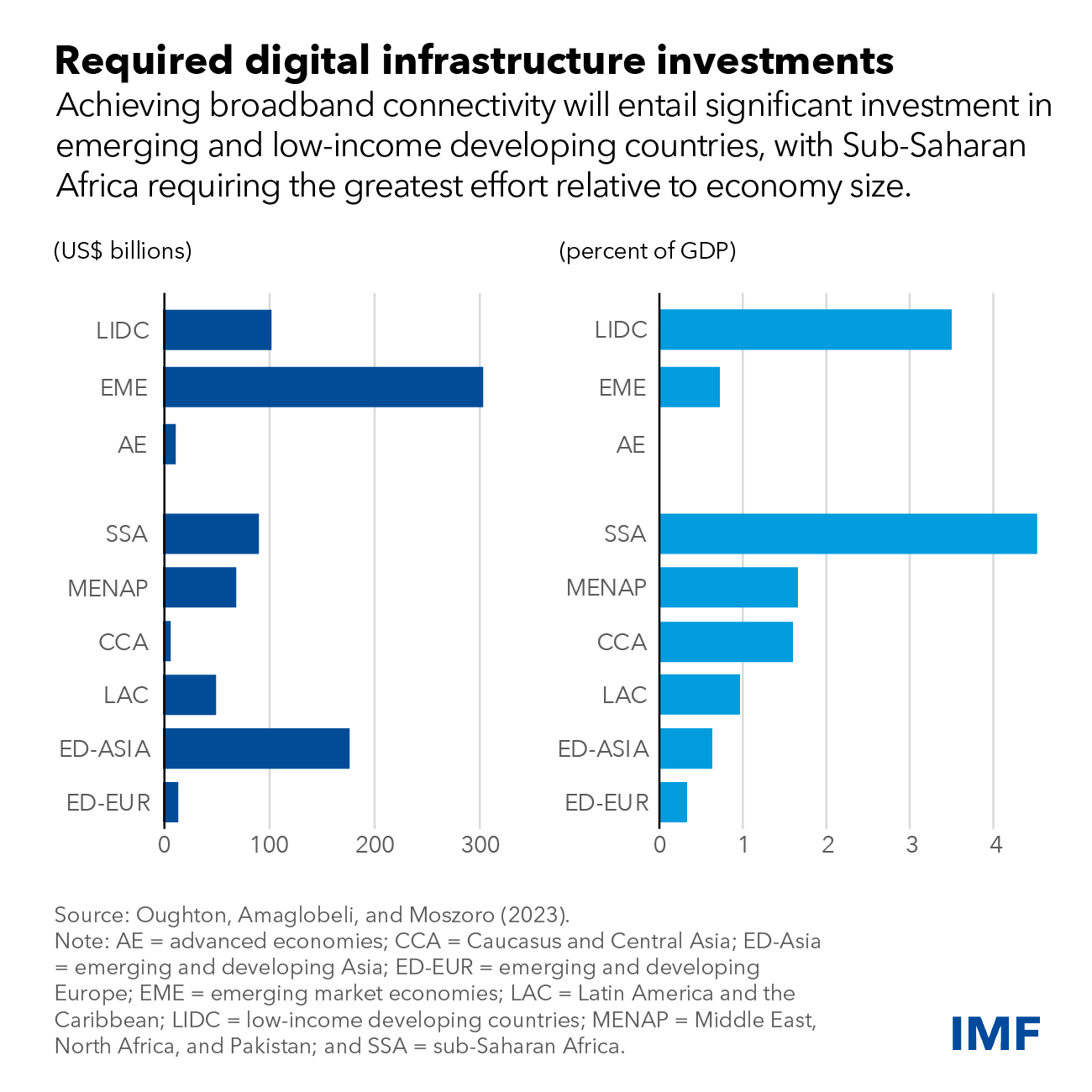

Our estimates show that $418 billion of investment in digital infrastructure is needed to connect unconnected households. The bulk of these investment needs are in emerging market and low-income developing economies, with the latter’s requirements estimated at 3.5 percent of GDP. Government support can be crucial in achieving universal connectivity by incentivizing or directly investing in building internet infrastructure, especially in regions where profitability remains challenging.

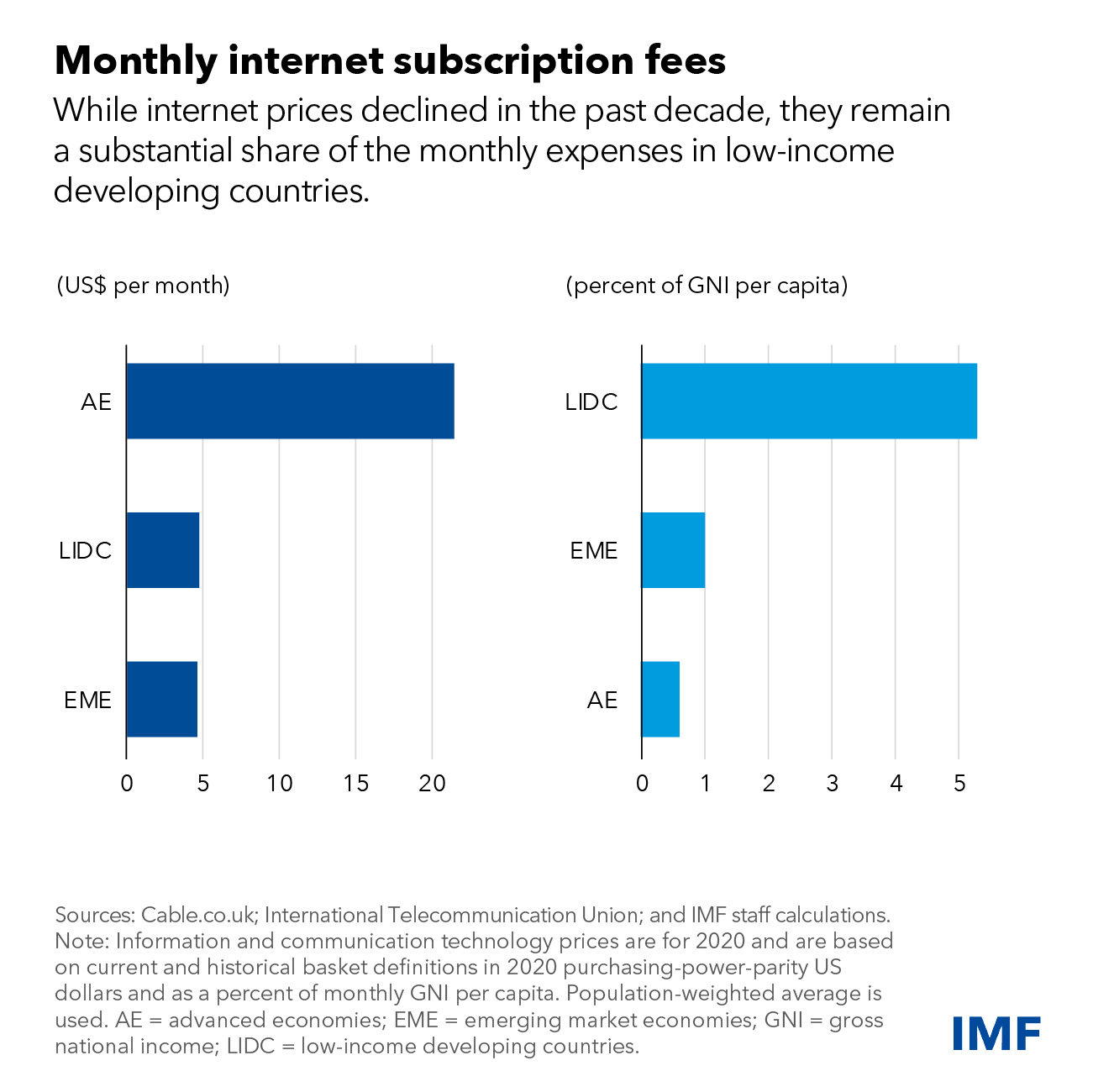

In addition to infrastructure, affordability and digital literacy are crucial. Internet subscription costs remain high in low-income developing countries, where, relative to average incomes, the average cost is nine times the amount citizens in advanced economies spend. To make internet access more affordable, governments can consider offering discounts or vouchers on subscription fees. Additionally, promoting digital literacy programs is essential to overcome reluctance among specific populations, particularly older individuals, to embrace new digital technologies.

The Power of govtech:

Digitalization enables governments to leverage technology to enhance revenue collection, improve efficiency of public spending, strengthen fiscal transparency and accountability, and improve education, health-service delivery, and social outcomes. These can be achieved through better decision-making processes, adoption of international standards and practices, transformation of public financial management processes and systems, and improved taxpayer and trader services to support voluntary compliance and trade facilitation.

Adopting govtech in fiscal operations can strengthen public finance on both revenue and spending sides. IMF staff analysis shows that e-filing, e-invoicing and electronic fiscal devices could lead to a significant increase in tax revenues. For example, the adoption of e-invoicing and electronic fiscal devices could improve revenue mobilization by up to 0.7 percent of GDP. Digitalization’s impact on revenue administration is enhanced by expanding digital connectivity and ensuring sufficient staffing and expertise among tax officials. Similarly, the automation of budget payments using digital technologies is associated with more budget transparency. Our analysis suggests that digitalization is generally associated with an improvement in the efficiency of expenditure.

Digitalization can also improve the effectiveness of social spending and the quality of public service delivery. Digital interventions, such as providing students with equipment and software, can improve education outcomes. In healthcare, govtech can help improve quality of care, increase the coverage of underserved populations, and optimize resource utilization. Electronic health records, telemedicine, and digital platforms for patent licensing, procuring medicine, and monitoring infectious diseases are areas of digital innovation in health care.

Digitalization can also help strengthen social safety nets through better identification, verification of eligibility, and provision of delivery mechanisms. For example, integrating digital ID and creating extensive socio-economic data can enable governments to better target and accurately verify beneficiaries receiving social assistance.

But these benefits from digitalization can materialize only if it is done right. Implementing large digitalization programs is a complex undertaking and requires careful planning, adequate resources, political support, and appropriate change management processes. Digitalization may require changes in regulations and established processes, adequate staffing and expertise among officials, and strong safeguards for data security and privacy to protect sensitive information. Without adequate safeguards, implementing complex digital solutions could even be counterproductive and facilitate corruption.

By adopting an approach to digitalization where citizens’ needs are the primary focus and engaging in close collaboration with stakeholders, govtech can help overcome these challenges and unlock its full potential to enhance public services for society. The IMF stands ready to support countries through its capacity development in implementing govtech solutions for public finance.